When I started this semester of college, I can’t say that I was expecting to spend a Saturday afternoon crouched in the snow, smelling the urine left behind by a fisher. Or building the biggest, most insulated snow fort I have ever seen. Or chaining seven sleds together with nearly fifteen kids and one adult. But there I was, on a freezing cold weekend when I could have been curled up with a cup of cocoa, my nose inches away from the yellow snow I had always been told to avoid.

It all started with a brief mention that I was free Saturday, and my internship supervisor at Primitive Pursuits assigned me to shadow the Coyote Howl teen program. She warned me to bring snow pants, mittens, and all the layers I could pack. I stuffed all the things I thought I needed into my worn-out blue backpack and headed to the 4-H Acres. Although I’m nearly ready to graduate college, I slipped back into the mindset of a new kid in 9th grade — will they like me? What if I don’t fit in? What if they don’t like my snow coat or my haircut? How do I talk to them? I hope they like me. I tried to put my misgivings behind me as we headed to sit in a circle in the snow. Danielle, one of two program leaders, kicked off the conversation by encouraging us to look around, connect with the land and each other, and let our gratitude for the land and its people vibrate through our bones. The theme of connectivity wove through the entire six-hour program; we were continually challenged to consider our relationship to the land.

“As we leave our footprints, remember that they are prayers, and intentions, and caretaking, and stewardship, to love and appreciate the land,” Danielle told us. She acknowledged the Cayuga Nation and its past and present Indigenous peoples as well, impressing upon us the importance of their contributions and the gravity of historical white violence. Sean, the other program leader, taught us a song after we all introduced ourselves.

It was haunting and more beautiful than I anticipated, coming from the throats of a handful of teens with no instruments except their mouths:

Ever a stronger basket, we’ll weave it ’round and through

And with a cry of “To the Meadow!” we were off, trudging through the sleek, packed snow, sleds and shovels in tow. We approached a big field of untouched snow, and even to my “mature” mind, it looked like it was in desperate need of gleeful trampling and snow-throwing.

Sean taught us how to make quinzee shelters, and within half an hour, we stood facing a mound of snow ten feet tall and ten feet wide. We tossed sticks onto the sides and shoveled more snow on top, and then we sent the brave ones in to dig out the inside, one at a time. The eerie blue light filtering through the walls of the shelter reminded me of being underwater in the Arctic. I didn’t stay too long in the shelter. But one brave teen volunteered to be buried alive, so we sent her in with a thermometer and sealed the door with snow.

“Scream,” another teen yelled in at her through a small air-hole. A muffled “What?” came as reply.

“Scream!” several more teens yelled. A pause, and then the quietest “aaaaaaahhhhhhh” I have ever heard barely emanated from the shelter. Danielle and I exchanged nervous glances while the rest of the kids rolled laughing in the snow.

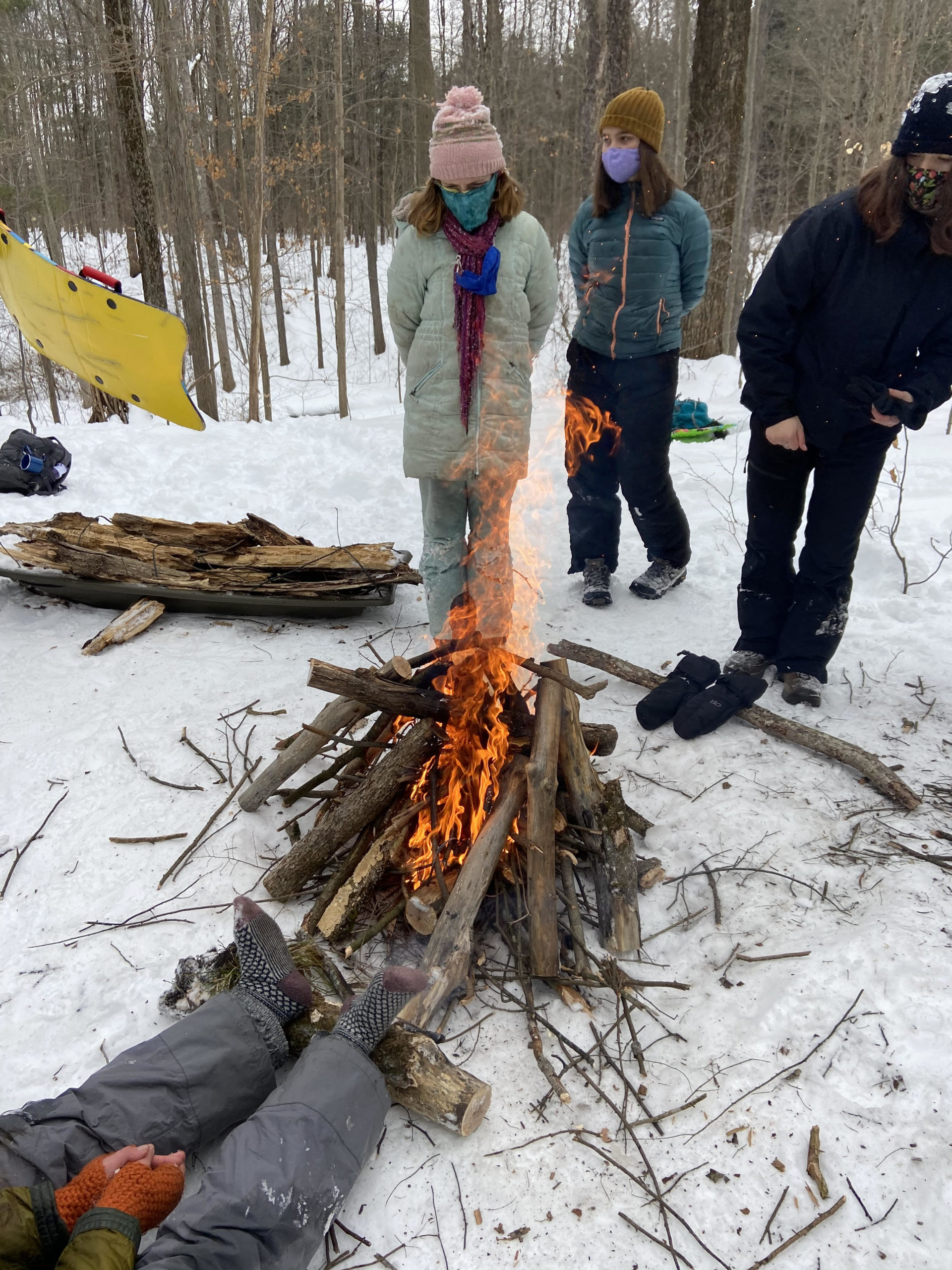

Afterward, we wandered the snow-covered woods, feet frozen into bricks in our boots, and gathered firewood. We found fisher tracks, smelled the scent mark to double check, and even found hair in the packed patch of snow. The walk back to the campfire was more of a stomp as I tried to return feeling to my poor, cold feet. And my jaw dropped as I watched Astrid, with one match and a handful of snow-covered twigs, stir up a blazingly hot fire within minutes. No structure, no architecture — handfuls of sticks were dumped onto the flame, a big log rested on the bottom, and soon enough my feet were out of their boots, the cold steaming from the socks. My snow pants and socks have holes singed in them from the embers that landed, but that was a small price to pay for the painful feeling of heat worming its way back into my bloodless toes.

Then, after helping chop frozen vegetables into a massive pot, it was time for what everyone had been waiting for with bated breath: sledding. The minute the word was mentioned, boots were on socked feet quicker than you could blink and butts were planted on plastic, soaring down the nearest hill we could find. We built jumps. We tried daring tricks. We screamed down the hill and giggled back up. Hats went flying, gloves sailed in different directions, bodies tumbled everywhere. Luckily, I was the only unlucky one catapulted into the creek, which was blessedly frozen solid. And for our final run, we got daring: a massive train of every single sled, strung together two-by-two like a horse-drawn carriage or the animals trampling into Noah’s Ark.

My friends, we flew down that hill.

And as we all tramped back to the fire, ate fire-cooked soup in mismatched pots, and circled up to say goodbye, we realized that we were more connected — to ourselves, to each other, to the earth itself — than we would have been in any other place but that one.